Search

Types of ID systems

The focus of this Guide is on ID systems that provide proof of legal identity that is often required for—or simplifies the process of—accessing basic rights, services, opportunities, and protections. Historically, governments have operated a variety of ID systems to serve this and other purposes. Primarily, this includes foundational ID systems, such as civil registers, national IDs and population registers, which are created to provide identification to the general population for a wide variety of transactions. An ID system can be considered legal ID system to the extent that it enables a person to prove who they are using credentials recognized by law or regulation as proof of legal identity—i.e., most foundational ID systems (see Box 4).

In addition, governments have often created a variety of functional ID systems to manage identification, authentication, and authorization for specific sectors or use-cases, such as voting, taxation, social protection, travel, and more. In some countries—and particularly those that do not have a foundational ID system beyond civil registration—functional identity credentials are used as de facto proof of identity for purposes beyond their original scope. In the United States, for example, social security numbers and driver’s licenses in the United States are issues as proof of authorization for specific purposes but are used as general-purpose credentials. However, functional ID systems are typically not considered to be legal ID systems unless they are officially recognized as serving this purpose.

|

Box 4. Defining “proof of legal identity” Proof of legal identity is defined as a credential, such as birth certificate, identity card or digital identity credential that is recognized as proof of legal identity under national law and in accordance with emerging international norms and principles. Legal identity is defined as the basic characteristics of an individual’s identity. e.g. name, sex, place and date of birth conferred through registration and the issuance of a certificate by an authorized civil registration authority following the occurrence of birth. In the absence of birth registration, legal identity may be conferred by a legally-recognized identification authority; this system should be linked to the civil registration system to ensure a holistic approach to legal identity from birth to death. Legal identity is retired by the issuance of a death certificate by the civil registration authority upon registration of death. In the case of refugees, Member States are primarily responsible for issuing proof of legal identity, including identity papers. The issuance of proof of legal identity to refugees may also be administered by an internationally recognized and mandated authority (1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees Articles 25 and 27). Source: United Nations Legal Identity Expert Group (LIEG) and World Bank Operational Definition of Legal Identity, 1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees. |

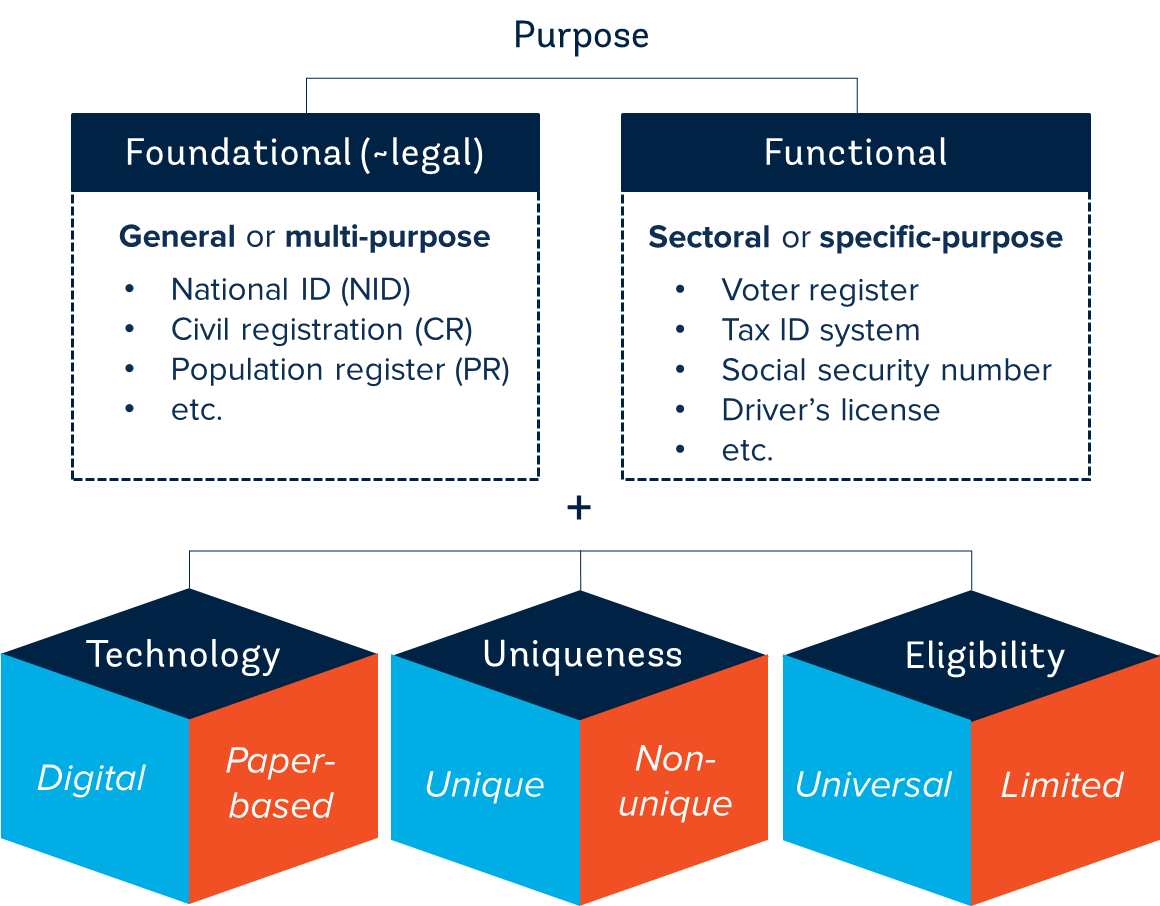

As shown in Figure 4, both foundational and functional ID systems vary along multiple dimensions, including:

-

The technology they use;

-

Whether they establish uniqueness; and

-

Who they cover in the population.

Figure 4. Classification of government ID systems

In terms of technology, these ID systems can be paper-based or digitized. Digital ID systems are those that use digital technology throughout the identity lifecycle, including for data capture, validation, storage, and transfer; credential management; and identity verification and authentication. Although the term “digital ID” often connotes identity credentials used for web-based or virtual transactions (e.g., for logging into an e-service portal), digital IDs can also be used for stronger in-person (and offline) authentication.

In addition, these ID systems may or may not uniquely identify individuals within a given population. Uniqueness typically means that (a) one person does not claim multiple identities within the system, and (b) each identity is only claimed by one person. In general, most foundational and functional ID systems are intended to be unique. However, some may have less reliable identity records due to a lack of deduplication, non-unique identifier generation (e.g., recycling ID numbers over time), or weak identity proofing procedures. In other cases, allowing for multiple registration may be a feature of the ID system functionality. For example, the same person can enroll multiple times in the UK’s Verify system, because its focus is on proof of identity, with any issues of uniqueness handled by the relying party, as described in Box 38.

Finally, these ID systems also vary based on the population that they are intended to cover. Because the purpose of foundational systems has been to provide broad (or universal, in the case of CR) coverage within the population, they are typically more inclusive in scope than functional systems, which—by their nature—are often limited to a certain subset of the population (e.g., people eligible to vote, beneficiaries of a cash transfer, people who have passed a driver’s test, etc.). In some cases, however, functional ID systems have relatively broad coverage because their program is intended to be universal (e.g., the US social security number). Similarly, not all foundational ID systems cover the entire population. For example, a country’s civil registry only covers vital events that occur within the territory, and therefore does not cover migrants or (in some cases) nationals born abroad. Similarly, some national ID systems only cover nationals, foreign residents with a valid visa, and/or people over age 18. In contrast other countries have implemented inclusive foundational ID systems that are accessible to all people within a territory or jurisdiction.

Within a given jurisdiction, there are normally many government and private-sector ID systems that together make up the identity ecosystem. As ID systems become digital, these ecosystems may be increasingly complex, with a wide range of identity models and actors with diverse responsibilities, interests, and priorities. The particular path that a country takes to develop a digital identity ecosystem will depend on a variety of factors, including which ID systems and assets already exist, and the identity-related needs of key stakeholders in both the public and private sectors.

Role of a foundational ID system

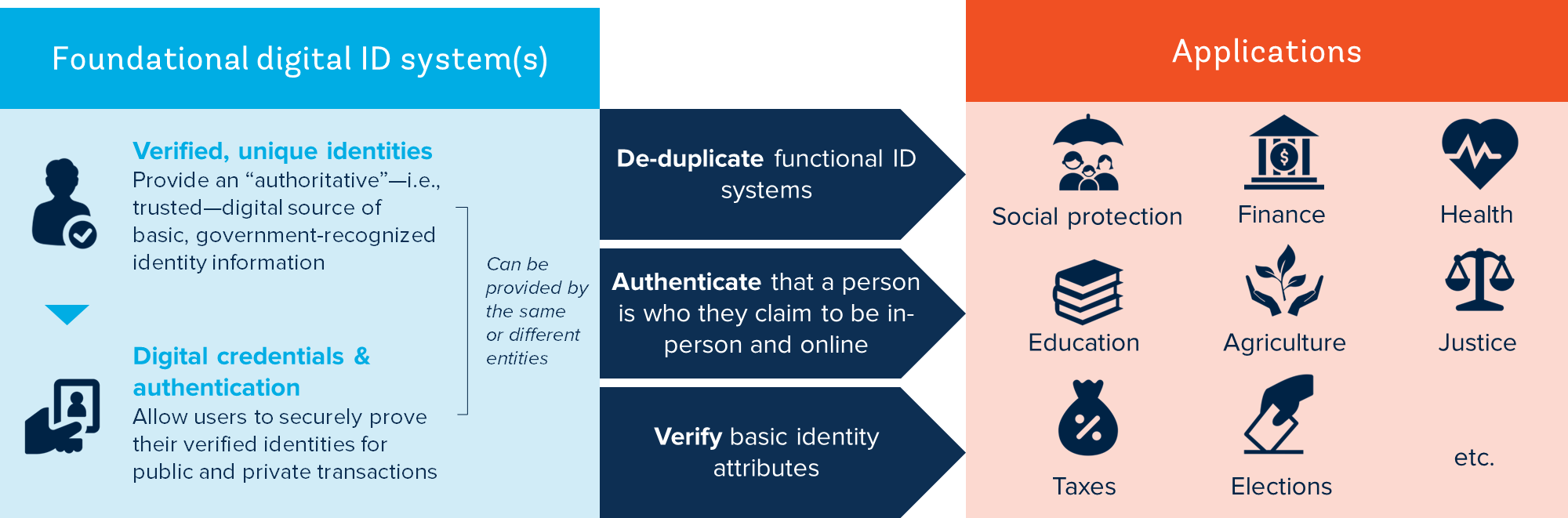

The focus of this Guide is on the design and implementation of foundational, digital ID systems that provide people with proof of legal identity. As shown in Figure 5, inclusive and trusted foundational ID systems can serve two important functions within the identity ecosystem and across a variety of sectors:

-

Authoritative source(s) of basic identity information. By creating a register of unique, verified identities, a foundational ID system can provide the basis for secure identity verification for government and private-sector users. In any country, having one or more trusted sources of basic identity information is vital to the integrity of the identity proofing process for government functional ID systems and for private-sector ID providers and relying parties (e.g., financial institutions or MNOs conducting KYC). Beyond the verification of identity attributes themselves, a foundational system with unique identity records can also help deduplicate functional systems—e.g., a cash transfer register or public payroll—reducing opportunities for fraud and the need for redundant data collection by the foundational system (see Public Sector Savings paper).

-

Credential and authentication provider. In addition to establishing an authoritative source of identity information that can be leveraged by other systems, foundational ID systems can also provide credentials that allow people to authenticate their identities for a wide variety of purposes and sectors. As with verification, authentication can be a shared service provided to a variety of public and private sector users. When built as a platform that allows users to leverage the ID systems’ credentials and authentication rather that building their own, this can help reduce costs for government agencies and private companies (See Private Sector Savings paper).

As described in more detail in the Introduction, having one or more interoperable foundational ID systems that serve these functions can improve access and service delivery across a variety of sectors, including health, education, social protection, financial inclusion, etc.

Figure 5. Potential role of a foundational ID system

Source: Adapted from Digital Identity Toolkit

In order further these development goals, however, foundational ID systems must be inclusive, and they must be trusted. In accordance with SDG 16.9 and the Principles for Identification, all people must have access to proof of their legal identity, no matter their age, nationality, or where they were born. CR systems are an important part of this infrastructure and provide the authoritative source of certain attributes as they were at the time of birth or death (i.e., at the moment births or deaths were registered) assuming that they were accurately recorded. Some of this information (e.g., name, legal guardians, and sex) could change over a person’s lifetime, while other attributes (e.g., date and place of birth or death, and birth parent’s identities) are immutable. However, CR systems are not dynamic registers of identity data, and—because they only cover events that occurred within the jurisdiction—they cannot be an authoritative source of information for people who were born elsewhere or who never had their vital events registered.

Providing legal identity for all therefore requires the strengthening of CR systems alongside—and in coordination with—the development of ID systems that can leverage and build on the CR while adding functionality (e.g., identity proofing, online verification and authentication services, portable credentials, etc.). In addition—and as enshrined in Principles 1 and 2, countries must ensure that everyone has access to foundational ID system, regardless of who they are. This requires a conscious and continuous efforts to remove or mitigate barriers to accessing proof of identity that are common among vulnerable populations.

In addition, foundational ID systems will only achieve the benefits described above when they are trusted—both by people and the institutions and companies that rely on them. Where people do not trust the provider of an ID system to manage and protect their data, they are unlikely to participate. Systems with low coverage have limited utility for governments or people and will necessitate parallel business processes to deal with people who are and are not covered. Similarly, where the data or credentials provided by an ID system are known or perceived to be inaccurate or susceptible to fraud or tampering, service providers will not be able to take this information at face value. Effective public engagement, robust legal frameworks, and a privacy-and-security-by-design approach are therefore fundamental to ensuring the overall success of the system.

New models for foundational ID in a digital world

In the past, most foundational (and functional) ID systems were paper-based and operated or managed entirely by governments. With the move toward digital technology throughout the identity lifecycle, however, we have begun to see new models of partnerships or trust frameworks between governments and the private sector to provide digital layers on top of existing legal ID systems that are recognized by the government for official online transactions. Typically, these systems leverage existing government-owned identity registers as authoritative sources of information to provide digital authentication and verification services for both official purposes and private sector applications.

A number of authors—notably from ITU (2018) and WEF (2016)—have developed typologies to categorize these new digital ID ecosystem models, typically based on the role of the private sector in providing digital identities, and the structure of these arrangements (e.g., federation). For the purpose of this Guide, it is also important to distinguish an additional dimension beyond the number and type of digital ID (i.e., credential and authentication providers), which is the type of authoritative source(s) these digital ID use for identity proofing. Using these dimensions, we can classify various models used to provide people with government-recognized or legal identity in a digital form:

-

Centralized: Under the centralized model, there is a single provider for a digital ID system recognized by the government as providing proof of legal identity.

-

In some cases, this may be the same entity that maintains the authoritative source register (e.g., a national ID or population register) on which the digital ID is based (e.g., Belgium’s eCard, Netherlands’ DigiD, India’s Aadhaar, and many others).

-

In other cases—i.e., where there is no foundational ID system—the official digital ID may be provided by an entity that relies on multiple functional or lower-tiered government ID systems as authoritative sources for identity proofing (e.g., the current myGovID system in Australia).

-

-

Federated: Under a federated model, multiple entities provide a government-recognized digital ID, coordinated or accredited through a trust framework or federation authority.

-

In some cases, these identity providers are public and/or private entities and that leverage a foundational ID system as their authoritative source (e.g., Bank ID in Sweden, Norway, and Finland, NemID in Denmark, Belgium’s Itsme®)

-

In others, they draw from multiple functional systems as well as civil registers through a “broker” or federation authority (e.g., GOV.UK Verify, Canada’s SecureKey).

-

-

Open-market: Finally, countries could have multiple, regulated entities that provide government-recognized digital ID based on multiple functional IDs and or civil registers as authoritative sources of identity. In contrast to the federated system, however, these providers operate based on bilateral agreements with individual government agencies that provide online services rather than through a central or brokered scheme (e.g., U.S.).

In addition to the government-recognized forms of digital identity discussed above, countries may have a host of other digital ID systems maintained by public or (primarily) private sector entities for their internal use and for unofficial purposes. This might include, for example, private-sector-provided IDs that are derived directly from the government-recognized authoritative sources or digital IDs described above, issued after identity proofing based on non-governmental sources, or self-asserted (e.g., social media, email accounts, commercial platforms, etc.). In addition, there are emerging models of decentralized or distributed-ledger-based digital identity that seek to put people—rather than ID authorities, providers or relying parties—in control and at the center of identity transactions. However, distributed digital identity solutions typically rely on official data sources (i.e., foundational and/or functional government systems) to substantiate basic identity attributes in the first instance. To our knowledge, such models have not yet been accepted as legal proof of identity for use in official (online or in-person) transactions.

Importantly, different models of digital ID can exist within the same jurisdiction—in Belgium, for example, people can log-in to online government services using either the centrally-provided eCard, or the Itsme® digital ID (the first certified credential provider in an emerging federated scheme). This can improve people’s control over their digital identities by offering them a choice of providers (and the ability to switch to more trusted or user-friendly services as needed).

The ideal model of providing a digital, government-recognized ID system is very country-specific, and depends on the country’s historical development, the trustworthiness of existing registers and other authoritative sources of identity information.