Search

Proofing identity claims

Once identity data has been collected through the registration process—i.e., people have “claimed” a particular identity by completing an application and providing supporting evidence—it must be “proofed” in order to determine its veracity. Identity proofing enables the ID provider to:

-

Resolve a claimed identity to a single, unique identity within the context of the population

-

Validate that all supplied evidence is correct and genuine (that is, not counterfeit or misappropriated)

-

Validate that the claimed identity exists in the real world

-

Verify that the claimed identity is associated with the real person supplying the identity evidence (NIST 800-63A:2017)

The identity proofing process is fundamental to ensuring the accuracy and trustworthiness of the identities created. In addition, the requirements for identity proofing have important implications for how convenient and resource-intensive the registration process is, which in turn affects both the inclusivity and cost of the program. This section focuses on relevant choices regarding fundamental processes of the identity proofing phase of registration:

-

Validation. Checking the validity, authenticity, and accuracy of the supporting documents or evidence provided and confirming that the identity data is valid, current, and related to a real-life person.

-

Deduplication. Using biometric recognition (using biometric identification to identify other identities already registered that could be a match) and/or demographic deduplication algorithms—e.g., fuzzy logic—to ensure that a person is unique before they are enrolled.

Figure 24. Key considerations for identity proofing

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Inclusion | Reliability | Sustainability |

| Marginalized groups may not always have supporting documentation to prove their identity, and complex registration and proofing requirements may present financial and logistical barriers | The strength of the deduplication and validation processes will determine the accuracy and uniqueness of identities and contribute to the level of assurance for transactions | Extensive identity proofing requirements will add time and expense to the registration process |

Validation

Validation creates confidence that the identity information contained about a person in the ID system reflects who they really are. By determining the authenticity, validity, and accuracy of the identity information the applicant has provided on the application, the identity provider can be reasonably sure that the identity is “real” and “correct.” Robust validation may require a variety of processes involving several types of evidence, investigative measures, and technologies, as shown in Table 31.

Table 31. Example measures and technologies used in identity validation

| Measure | Description | Potential Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Requiring supporting documents | Applicant presents one or more acceptable documents, such as birth certificates, passports, driver’s licenses, voter IDs, property titles, tax ID, ration cards, school ID, utility bills, etc. |

|

| Verification/ validation against external sources | Validation of the applicant’s identity and/or the validity of supporting documents by checking against other databases and systems, such as the civil register, social security records, local community records, etc. |

|

| Community witnesses or affidavits |

Testimonials from trusted community members or organizations who can act as a witness—either in person or in writing—to the existence of a person and/or specific attributes (e.g., village of birth) |

|

| Digital footprints |

Increasingly, people leave behind a digital trail or “footprint” based on their transactions and interactions, which can potentially be used as evidence for a person’s identity. To our knowledge, however, this method has not been used for a foundational ID system and would require a serious data protection impact assessment. |

|

Source: Adapted from the Digital Identity Toolkit

Ideally, all persons should be documented in the civil registration system at birth or upon entry into the country, providing an authoritative source of identity information and documents. Unfortunately, this is not the case in many countries, where many people often lack basic documents—e.g., birth certificates, passports, utility bills, driving licenses, etc.—to validate or verify their identity at the time of registration. Refugees and migrants who were not born in the country where they reside will not—by definition—be included in the country’s civil register. Many vulnerable people—particularly poor, rural, and slum dwellers—may also not have formal addresses or a reliable proof of their location of residence. Even if people do have some form of documentation, it may not be trustworthy if these documents are easy to forge or counterfeit.

In such cases, countries have developed alternate mechanisms to ensure that registration in foundational ID systems is inclusive, including the following (see Box 33):

-

Accepting a wide variety of supporting documents: If a certain document—e.g., a birth certificate or voter card—does not have universal coverage within the population, it should not be the only acceptable proof of identity for the registration process. Instead, countries can allow for substantiating documents from a variety of sources (e.g., Peru, India, UK Verify). In Malawi, different documents were given different reliability “scores,” and applicants for the national ID could provide various combinations of documents to reach the required threshold (see Malik 2018).

-

Decoupling nationality from identity: Providing proof of nationality is often one of the most arduous documentation requirements for ID systems, particularly in countries with jus sanguinis nationality laws (see ID4D’s The State of Identification Systems in Africa for some examples). Where the goal of an ID system is primarily to facilitate service delivery and online authentication for all people within the territory, nationality may not be directly relevant. In India, this choice significantly simplified registration timelines, reduced costs, and helped with the rapid uptake of the Aadhaar system.

-

Using reliable people to vouch for a person’s identity: Certain countries use an “introducer” or “witness” who can verify the applicant’s identity or particular attributes (e.g., residence or birth in a particular village). In India, for example, people without supporting documents can rely on a pre-registered introducer to assert their identity, and applicants who can demonstrate that they are the head of household can effectively serve as “introducers” for their family members. This model, however, requires that introducers frequently travel to registration centers, which may not always be feasible if they have full-time jobs. Furthermore, to ensure inclusivity, introducers must be available to all, and particularly to the vulnerable and marginalized groups that are most likely to need them.

A combination of the above strategies could also be used to allow for identity proofing at different levels of assurance (see Section III. Standards).

|

Box 33. Examples of inclusive identity proofing processes India’s Aadhaar system aimed for an inclusive and risk-based approach to registration to maximize the coverage and utility of the system while minimizing costs. Importantly—because Aadhaar does not provide legal proof of nationality—no documentation of nationality was required. In addition, low birth registration rates meant that enrollment agents were allowed to accept any of 18 documents for proof of identity, 34 documents for proof of address, and 9 for proof of date of Birth. (For a list of acceptable documents, see Aadhar's List of Acceptable Supporting Documents for Verification). In addition, people without any supporting can use approved introducers to attest to their identity. This includes people with high credibility, and particularly those who work with vulnerable groups (e.g., social workers, employees of the Registrar, postal workers, teachers, hospital staff, local government officials, etc.). The accountability of the introducers is achieved through an approval process by UIDAI agents (Registrars), a central registry of introducers that records who they have introduced, and punishments for false assertions. (See page 29 of UIDAI’s regulations on introducers). In addition, those without documentation were able to get signed letters from Gazetted Officers (e.g., a senior official in the local government) with the applicant’s photo, their details, and the official letterhead and signature/thumbprint of the Officer. Although there were initial concerns about applicants submitting incorrect or fake names for Aadhaar, this has not been a significant issue. Although accepting many types of documents has facilitated inclusion, a large portion of the population (particularly the wealthy and middle class) has applied using passports, driving licenses, and other trusted documents. For many poor people, Aadhaar has been their first reliable form of identification and a source of pride, creating incentives to provide correct information. In addition, the Government widely disseminated the consequences of providing false information, such as accessing services with providers where they had previously registered under a different name as well as fines and potential imprisonment. Crucially, the reliability of the Aadhaar system and its ability to provide a high level of assurance is achieved through biometric deduplication to ensure that each person can only register once. Thus, even if they gave a false name, they are only able to register once, and can be authenticated as the same person over time. ------ Malawi has an extremely low level of birth registration. However, the country used a different approach to verification for the national ID card because is also provides legal proof of nationality. Malawi assessed the quality of existing IDs and created a points-based system, whereby different supporting documents or an affidavit of a local chief were given a score based on how trusted they could be for both identity and nationality. Even for those who could not meet the threshold there were administrative mechanisms to process their claim to an identity. For more information, see pp. 24-36 of Malik (2018). ------ Peru began its national ID (DNI) system requiring birth certificates for registration, however it experienced high rates of exclusion among vulnerable populations. After the initial rollout, Peru had targeted campaigns that authorized municipalities and Civil Registry and Electoral Offices to accept applications and reapplications from vulnerable populations with minimum requirements (e.g. witnesses of birth, doctor’s or midwife’s note, baptismal certificate, etc.). |

On the whole, the validation process can be costly, as it involves the collection—and typically scanning—of evidence, as well as its subsequent examination and validation through mechanisms that could include cross-referencing against external databases (birth or death registers, health records, etc.), forensic examination of documents to ensure they are not forged, and interviews with individuals and members of the community. The more data that needs to be validated (and the more robust the validation procedures are), the more expensive the exercise will be.

Thus, it is important to adopt a detailed policy on what constitutes acceptable vetting within a framework of risk tolerance. This should represent the shared vision of multiple stakeholders—including the community—as to how to best prove someone’s identity and the required levels of assurance for different use cases.

Deduplication

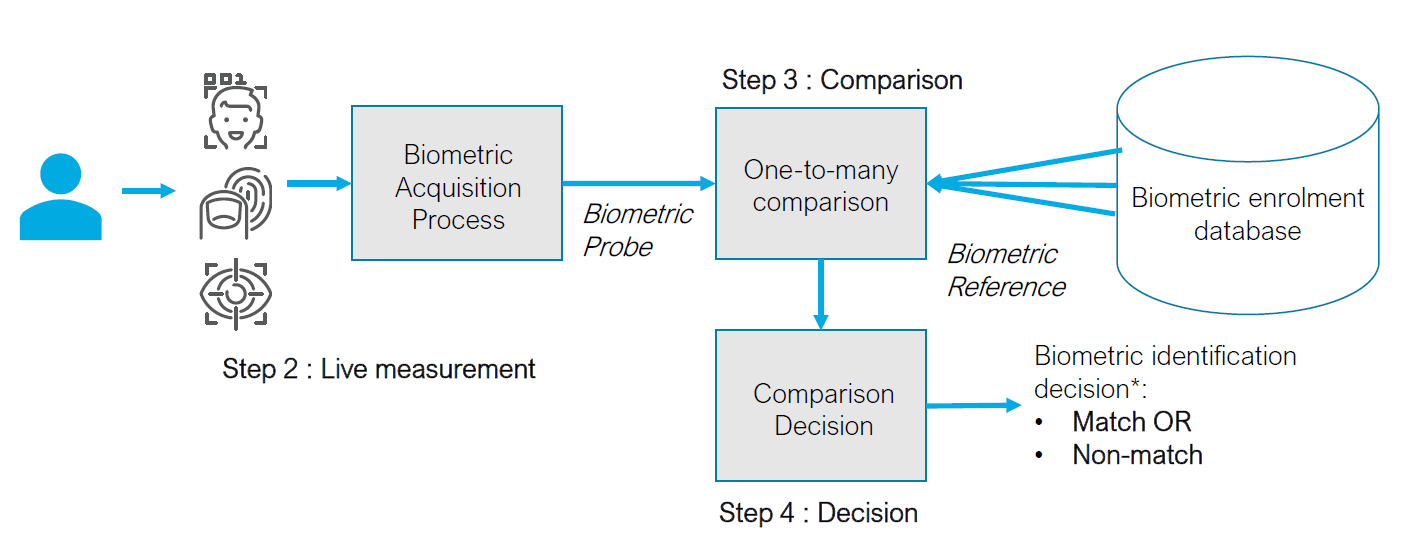

Once identity information is validated and enrolled, identity proofing typically continues with deduplication to ensure that each applicant is unique in the database. In the abstract, deduplication involves comparing a subset of the applicant’s data—e.g., core attributes and/or biometric templates—against all previously enrolled records (i.e., a 1:N or N:N matching process) to determine whether there is a match.

If no match is found, the identity is considered new or “unique” and is passed on to the next phase (e.g., registering the person and assigning them a unique number). If, on the other hand, a match is found, it means that this person may have previously enrolled. An adjudication process is then performed by a trained operator to validate whether the computer-identified match is an error (a false-match) or a genuine duplicate (i.e., the person has already enrolled). This type of deduplication process helps ensure the uniqueness of each record in the database.

Currently, biometric recognition is the most accurate technology for deduplicating identities, particularly in large countries where many people many share similar biographic attributes. This process uses a search engine called an Automated Biometric Identification System (ABIS)—or an Automated Fingerprint Identification System (AFIS) if using only fingerprints—to perform duplicate biometric enrollment checks of each new applicant (see Figure 25). The AFIS/ABIS is a complex and computationally intensive system that requires in-depth knowledge of biometric systems, IT systems, cybersecurity, and operations. Note, however, that biometric deduplication is rarely 100 percent automated and, in some cases, requires manual adjudication or verification by a human operator.

However, while biometric recognition may be the most advanced technology available for deduplication, it may not always be desirable, given the cost of the technology, potential issues related to inclusion, and data protection concerns discussed in Section III. Data > Biometric Data.

For more technical guidance on the use of biometrics for deduplication, consult the ID4D Biometrics Guide (forthcoming).

Figure 25. Example deduplication process using biometrics

Source: ID4D Biometrics Guide (forthcoming).