Search

Mutual recognition of IDs across borders

When IDs issued by one country are recognized by other countries—whether for face-to-face or online transactions—they become a powerful driver of economic and regional integration, including to promote safe and orderly migration. Importantly, ID systems can be mutually-recognized without the need for harmonization into a common system through the use of minimum standards to facilitate interoperability and legal and trust frameworks (e.g., for levels of assurance) to set rules and build confidence in respective systems.

A key use case is migration, through which a physical or digital identity credential can be recognized as a travel document in lieu of a traditional passport. In Latin America, for example, MERCOSUR member States recognize each other’s ID cards (which meet ICAO Doc 9303 standards as machine-readable travel documents) at borders in lieu of a passport, and a similar arrangement exists between Kenya, Rwanda and Uganda in East Africa. The benefit of recognizing cards from foundational ID systems as a travel document—particularly within regional blocs—is that they are more accessible and practical than a passport because people should have one by default, rather than a passport that requires a fee and often can only be applied for in major urban centers.

Another important use case is cross-border electronic transactions as part of the digital economy, which can be facilitated when a digital identity issued by one country is recognized for transactions online in another country. With an increasing number of transactions moving from face-to-face to online, and with the digital economy emerging as a key driver of economic growth, mutual recognition of digital identities between countries can accelerate trade in digital services and products and expand markets. For example, someone could open a bank account, register a business, and electronically sign contracts to trade in another country without ever needing to set foot in that country. The most notable example of this is the EU’s electronic Identification, Authentication and trust Services (eIDAS) regulation, which came into force in 2016 (see Box 42).

|

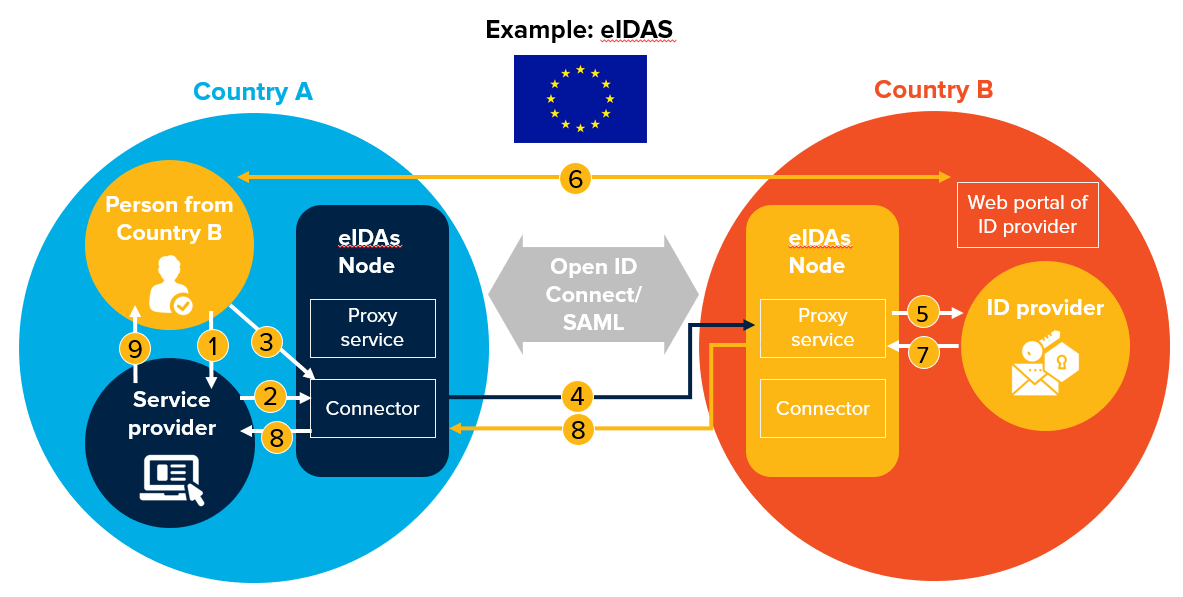

Box 42. The European Union electronic Identification, Authentication and trust Services (eIDAS) regulation eIDAS provides a predictable regulatory environment, standards, and governance mechanisms to enable secure and seamless electronic interactions between businesses, citizens and public authorities in the European Union. It ensures that people and businesses can use their national electronic identification schemes (eIDs) to access public services in other EU countries where eIDs are available. eIDAS also creates a European internal market for electronic Trust Services (eTS) by ensuring that they will work across borders and have the same legal status as traditional paper based processes. eID and eTS are key enablers for secure cross-border electronic transactions and central building blocks of the European The eIDAS Network consists of a number of interconnected eIDAS-Nodes, one per participating country, which can either request or provide cross-border authentication. Service Providers (public administrations and private sector organizations) may then connect their services to this network by connecting to the eIDAS node, making these services accessible across borders and allowing them to enjoy the legal recognition brought by eIDAS. It is the responsibility of each country to:

In practice, eIDAS means that people with a digital identity from a system notified by a member State to the European Commission can use that digital identity to access any service available online from any location. For example, a German can register a business or land in Malta or an Austrian can open a bank account in the France, using the IDs issued by their home country. Source: EU (2015). See https://www.eid.as/home/ for detailed information on eIDAS regulation and implementation. |

Several other regional blocs—notably the African Union (AU), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the East African Community (EAC) (see Box 43), and Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)—are now looking at options for mutual recognition of ID credentials across borders. Based on World Bank research, there are three broad potential architectures to facilitate mutual recognition while maintaining national sovereignty and without the need for harmonization:

-

Web-based. Online web-based authentication using federation protocol (SAML or Open ID connect); similar architecture used under eIDAS.

-

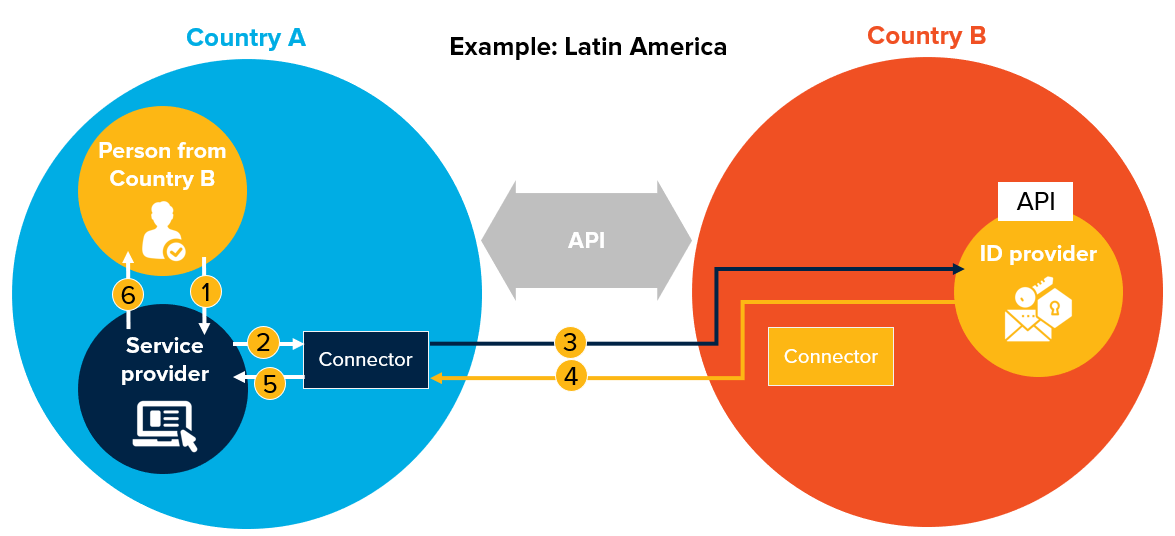

API-based. Online authentication using an API approach; similar architecture used among some Latin American countries.

-

Public-Private Key-based. Offline and online authentication verifying the private key on a credential against a public key directory; similar architecture used for the ICAO Public Key Directory of electronic passports.

The architecture and workflows of these three options are illustrated below in Figure 33, Figure 34, and Figure 35.

Figure 33. Web-based mutual recognition—example architecture and workflows

| Web-Based Mutual Recognition – Authentication Flow | Prerequisites |

|---|---|

|

|

Figure 34. API-based mutual recognition—example architecture and workflows

| API-Based Mutual Recognition – Authentication Flow | Prerequisites |

|---|---|

|

|

Figure 35. Offline mutual recognition—example architecture and workflows